There are three “big” Oscar-bound films that are opening in the month of November: Skyfall, which opens today; Silver Linings Playbook, opening on November 21st; and Steven Spielberg’s prestigious and well-reviewed historical pic, Lincoln, opening next Friday, the film we’ll write about today.

All, of course, demand to be seen — Skyfall, for its pure entertainment value, Silver Linings Playbook, because Jennifer Lawrence is the early odds-on favourite for a Best Actress Oscar, and Lincoln, because the reviews are universally praising and because, too, the film represents an unusually mature work by director Steven Spielberg, with Lincoln set as the film to consolidate and enhance his legacy as a 20th-21st century filmmaker of prominence, whose canon of cinema has influenced filmmaking and filmmakers perhaps more than any other in the past 40+ years.

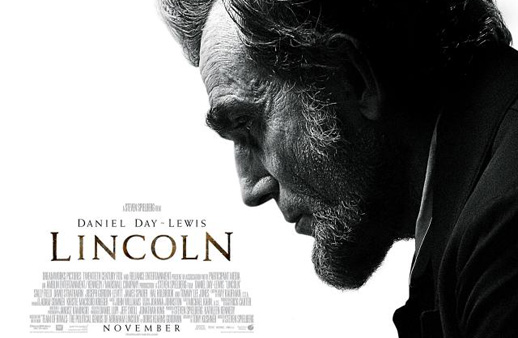

Lincoln, dir. Steven Spielberg, w/ Daniel Day Lewis & Tommy Lee Jones

Perhaps the best place to start in our preview exploration of Lincoln is Todd McCarthy’s first out of the gate review of Lincoln — Spielberg’s magnum opus — published on November 1st, in The Hollywood Reporter …

An absorbing, densely packed telling of the 16th president’s masterful effort in manipulating the passage of the 13th Amendment, Lincoln dedicates itself to doing something very few Hollywood films have ever attempted, much less succeeded at: showing, from historical example, how our political system works in an intimate procedural and personal manner, history that plays out mostly in wood-paneled rooms darkened by thick drapes and heavy furniture and, increasingly, in the intimate House chamber where the strength of the anti-abolitionist Democrats will be tested against Lincoln’s moderates and the more zealous anti-slavery radicals of the young Republican Party.

At the film’s centre lies one of the remarkable characters in world history at the critical moment of his life. As Walt Whitman said of Lincoln, “he contained multitudes,” and Daniel Day-Lewis’ sly, slow-burn performance wonderfully fulfills this description. Gangly, grizzled and, as his wife was known to say, “not pretty,” this Lincoln plainly shows his humble origins and is more disheveled than his Washington colleagues. With an astonishing physical resemblance to the real man, Day-Lewis excels when shifting into what was perhaps Lincoln’s most comfortable mode, that of frisky storyteller, especially in the way he seems to anticipate and relish his listeners’ reactions. But he also is a hard-nosed negotiator with that critical attribute of great politicians in a democracy: an unyielding inner core of principle cloaked by a strategic willingness to compromise in the interests of getting his way.

Andrew O’Hehir, respected film critic over at Salon.com, feels equally enthusiastic about Lincoln, as he writes …

Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field and an amazing cast bring history alive in Spielberg’s moral masterpiece. Spielberg has outdone Griffith and Ford and then some, crafting a thrilling, tragic and gripping moral tapestry of 19th-century American life, an experience that is at once emotional, visceral and intellectual. In a mesmerizing collaboration with a great actor (Day-Lewis) and a visionary writer (Pulitzer-winning playwright Tony Kushner), Spielberg has captured Lincoln as a shrewd political leader and a man of his time.

Is Lincoln an inspiring story of American greatness? Yes, absolutely. But if you say that, also say that it’s a cautionary tale of American mendacity and hypocrisy, the unfinished story of a cancerous evil that poisoned and divided America from its birth and does so still.

Meanwhile, Devin Faraci over at Badass Digest, who often tends to the cynical, offers an all out rave for Lincoln, when he writes, “Polish the Oscars, and warm up the accolades: this is the best Daniel Day-Lewis performance ever, and it’s one of the best Spielberg movies ever.” Faraci goes on to say:

Lincoln is an epic achievement. Smart, inspiring and bold, the film shows a vision for what government can be and what it can do. It presents a road map for sensible political compromise in the pursuit of historic and important goals. And it paints a compelling portrait of Abraham Lincoln as a flawed, imperfect man who was nonetheless a genius and a once-in-a-generation visionary.

Lincoln is one of the best movies of the year, and it’s one of the best movies of Spielberg’s career. It’s a film that speaks to his growth as a filmmaker; the bravest thing he does here is to pull himself back, to let the performances and the script speak for themselves, to act as a guide to this and not as a showman or a spectacle-maker. He has made a film that presents a mature, finely gradated examination of right, wrong and the murky place between them. And he has made it fun, and enjoyable. He has made a movie about thinkers and debaters for thinkers and debaters. He has made a movie where eloquence and conviction are the action elements, not chases and explosions.

He has made, simply, a masterpiece.

Many other (but not all) of the prominent British, American and Canadian film critics feel as O’Hehir, McCarthy and Faraci have indicated they do, that with the release of Lincoln, director Steven Spielberg has reached for and attained auteur greatness. Will audiences fill the same way? The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences most certainly will.

Although Lincoln opens in Toronto, New York and select other U.S. cities today, in Vancouver we will have to wait until next Friday, November 16th.